Introduction

First, we should be aware that we are talking here about moving money between people, between businesses and between people and businesses; we are not talking about bitcoins, blockchains or milk bottle tops.

The money we are talking about is the hard cash that we are happy to see represented by bits and bytes in bank (and other) accounts that we can see on our mobile phones and that we can withdraw and turn back into hard cash should we so desire.

We should also make sure that we are aligned on what we mean by an account.

What is an Account?

A bank account is a financial arrangement between an individual (or business) and a bank (or similar) that allows money to be safely stored, managed, accessed and moved.

At its core, a bank account is essentially a record the bank maintains of how much money you’ve deposited and withdrawn, and the bank uses these records to manage funds and provide financial services.

There are different types of bank account, but the main functions of each include:

- Depositing money → putting your cash or earnings into the account.

- Withdrawing money → taking cash out, either directly through ATMs, or electronically.

- Payments and transfers → paying bills, sending money to others, or receiving payments.

- Earning interest (some accounts) → banks may pay interest for keeping money with them.

- Providing access to financial services → debit cards, overdrafts, online banking, and credit facilities.

The most common types of bank account are:

- Current accounts → everyday spending, bills, and payments (checking accounts in the US).

- Savings accounts → designed to hold money and often paying interest.

- Business accounts → for companies to manage income and expenses.

In modern economies, a bank account can be considered a safe place to keep your money and a tool to move that money around.

In the following, we are focussing on the mechanisms and ecosystems that support the movement of funds from one account to another.

What is a Money Movement?

Within the framework of this discussion, we are defining a money movement as the transfer of funds that happen to reside in some sort of account, from one party to another party – in simple terms: as one account balance goes down, the other goes up.

There are essentially three Money Movement Models, but first, let’s confirm what is not going to be included.

- Closed Loop (private) payment systems, like the Stroud Pound

- Digital Wallets as they are representative of a presentation layer

- Crypto / Distributed Ledger as this isn’t (yet) about the movement of cash

All money movements within the banking system are account to account money movements where the nominal account, whether that be a personal account or a claim on a shared account, belongs to an individual or to a business. The reference to account-to-account transfers in the context of money movement models should not be confused with current A2A (account-to-account) payment propositions based around Open Banking.

Money Movement Models

Taking away all the abstractions, we’re left with the mechanics of regulated fiat money moving from one space to another, which collapses into three models:

- Bank rails – account to account money movement via central bank settlement

- Card rails – “on platform” account to account money movement but with bulk settlement

- Bucket of Money – value transfer from “account” to “account” but no money movement

Whilst the three money movement models may look similar on the surface – they all move money from one place to another – they all represent fundamentally different approaches to transferring value and have evolved over the years to what we see now.

At the highest level, each model describes how money is transferred from one account to another account, so it is not surprising to hear people taking the Jeremy Clarkson approach: it’s only a payment, how hard can it be?

Football and Rugby

Consider the following: football and rugby are team sports played on a similar sized grass surface with a similar number of players and ancillary officiating participants, a similar sized ball, a similar direction of unified travel and a similar goal of delivering the ball into the space defended by the opponents and doing so by avoiding or outsmarting those opponents.

Football and Rugby are similar in principle, but if you had yourself the perfect setup for a game of Football, with posts, pitch markings, officials and a ball, you could not use that setup to play Rugby – the principles, and therefore the rules, are fundamentally incompatible!

And think about the chaos if you were to attempt to play Football and Rugby on the same pitch at the same time!

But to the uninitiated, they can look very similar – so, how hard could it be?

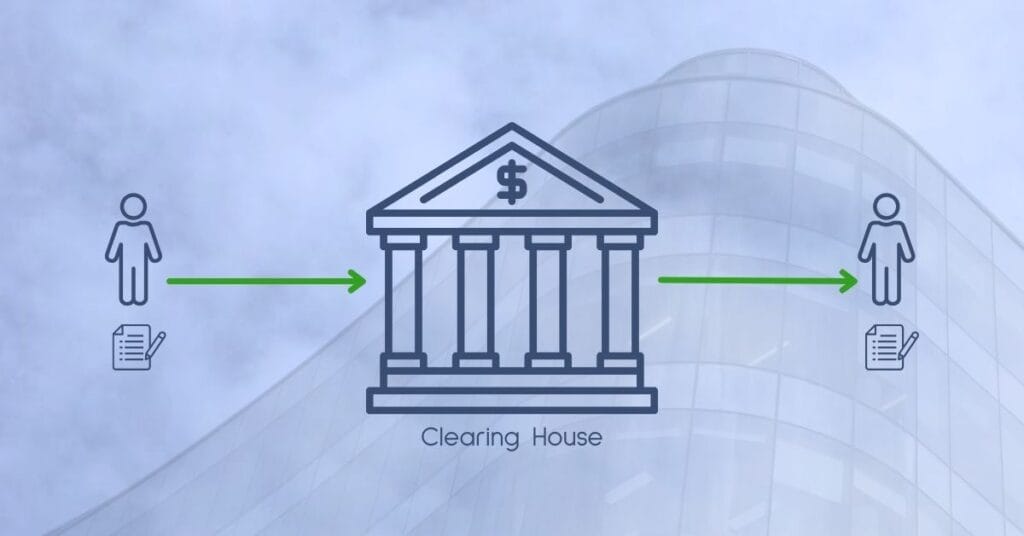

Bank Rails – account to account – personal

Wherever money is held electronically, it is a bits and bytes representation of some physical real-world hard cash, so the definition of an account is somewhat abstract. However, the physical real-world value that belongs to me is held in a real thing – called an account – that also belongs to me. I am the account holder, and it therefore follows that I have a direct relationship with my account.

Everyone with an account has a similar relationship with that account as the one I have with mine, so if I want to give my friend a tenner, for whatever reason, I can send a tenner from my account to my friend’s account. My friend receives this into their account, withdraws it in cash, and can then grasp the cash as if I had handed it to them myself.

The banking services infrastructure allows for the transfer of funds from any connected account to any other connected account, recognising that for bank-to-bank account transfers to be possible in the first place, the banks will usually need to be signed up to the same club and connected to the same hub.

Account-to-account value transfers are discrete push payments, initiated by the sending account holder using the sort code and account number to identify the receiving account. These transfers are ideal for one-off payments initiated by the sender, especially where the receiver is known to the sender and the transfer is not time-critical in a way that a retail transaction is.

Although not unheard of, the sender is unlikely to want to be sending multiple payments or payments in bulk, and similarly, the receiver is unlikely to need to be receiving multiple payments – I should make the distinction here between A2A push payments and Direct Debits (DD), and we’re not talking about DDs.

Receivers expecting to receive multiple incoming payments are likely to be businesses, they are also likely to be operating internal customer accounts that support repeat orders and repeat payments – subscription services, milkmen, window cleaners and of course, HMRC.

We should note that whilst Faster Payments appear to be instantaneous, they are settled several times a day in the background, they are only instantaneous because the member banks agree to make them so. For the following, we need to be considering the mechanisms operating above the settlement.

Card Rails – account to account – bulk

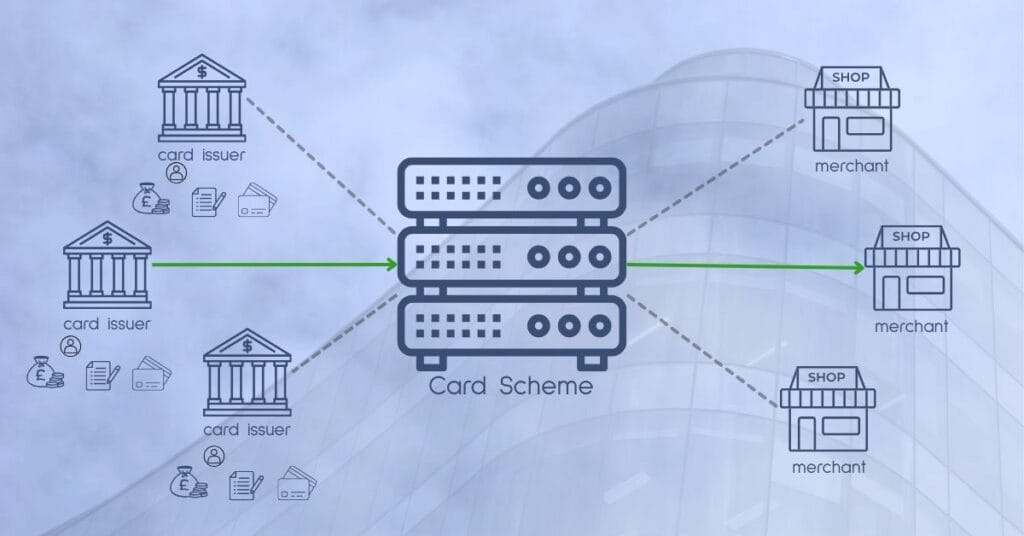

If we will establish that the logic of a card payment is comparable to the logic of a Faster Payment, then the difference between a card payment and a Faster Payment becomes the difference between knowing the account details of the recipient and not knowing the account details of the recipient, because for a card payment, that information isn’t required.

Card rails – the mechanics of card payments – do not move money around! The card schemes maintain a record of promises to pay, alongside a record of monies owed, and then aggregate the payments into a collective set of money movements, using the banking account-to-account infrastructure to settle in bulk sometime after the transaction completes.

Whilst these are the mechanics of card payments, we can usually see the balance of our bank accounts reduce as a payment is authorised, and for a merchant, an authorised payment is as good as cleared funds, although the reality is that the funds may be delayed in settlement – in the days of zip-zap machines and voucher imprints, a merchant was able to deposit a voucher over the counter and it would be treated as cleared funds.

The point here is that even though the money does not physically move immediately, the financial implications of a card transaction are immediate at both ends, and so we can reasonably consider the logic of a card transaction being similar to that of a Faster Payment – Faster Payment account-to-account transfers are “immediate” because the participating banks agree to fund the transfer before the Faster Payment is settled.

Card rails essentially extend the nature of a personal account-to-account transfer to a situation where neither party knows, nor really cares, who the other party might be. For example, customers know they are shopping at Tesco and because of this, they feel able to trust the technology in front of them … and on the other side, Tesco don’t care who I am so long as the little plastic card tells them that the account sitting behind the card is good for the cash.

The card schemes provide and support the global frameworks that allow both parties to a transaction to be comfortable in trusting the other, without extensive personal knowledge of the other party.

Card rails were designed, and have since evolved, to facilitate retail payments where each party – customer and merchant – has a need to pay or accept payments from multiple parties on the other side. These are one-to-many relationships where the banking-level account identities of the other parties are not known … or needed.

The card scheme infrastructure is the simplest and most efficient means of connecting multiple discrete entities – customers and merchants – for a time-limited, transient transaction, and the trust is with the card scheme.

“Bucket of Money” – ledger entries

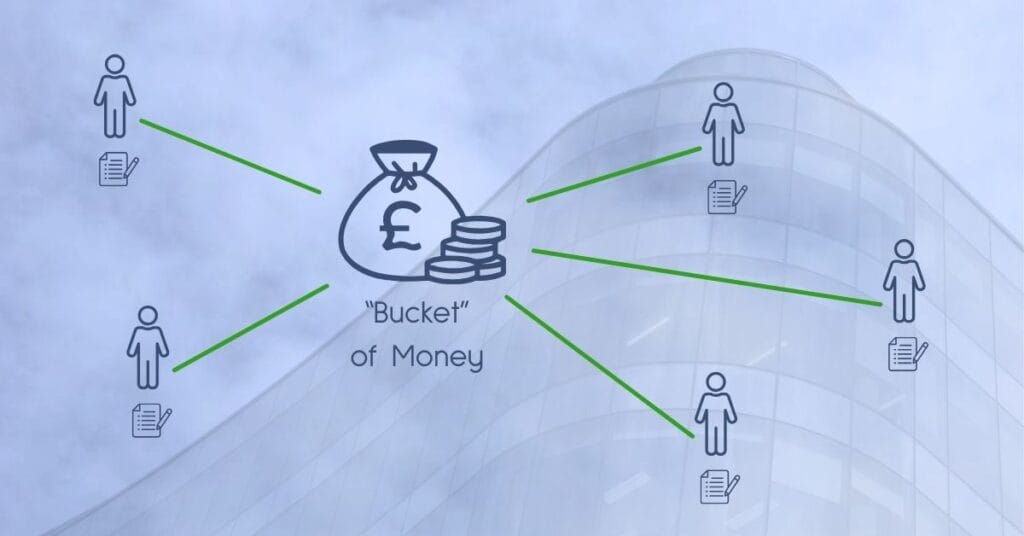

Whilst the Bank Rail and the Card Rail value transfer mechanisms are similar insofar as they both operate a model where the real movement of funds lags behind the apparent movement of funds, the “bucket of money” model, in contrast, sees no real movement of funds at all.

All the cash within the closed “bucket of money” system is held in the same bank account, with individual “account” holders only ever seeing their share of the collective pot, and there is little distinction between consumer and merchant.

Transfers of value between one party and another are simply bookkeeping entries that reduce the sender’s leger balance at the same time as increasing that of the receiver. It makes no difference if the transfer is person-to-person, person-to-merchant, merchant-to-person or merchant-to-merchant, and because of this, transfers across a bucket-of-money platform are instantaneous.

Should value need to be transferred to or from a third party outside the closed “bucket of money” ecosystem, then the value will be transferred via the banking processes described previously.

The value of the “bucket of money” model is in the economics. Internal value transfers are effectively free, and they are also very simple to initiate. The bucket of money is ideal for payments based around QR codes and similar.

Summary of Models

In all the money movement models, the perception of both the sender and receiver of funds is that the transfers are discrete and stand alone, which is what you would expect.

Under the surface, Bank Rail value transfers are essentially processed and settled individually in real time, Card Rail value transfers are processed in real time but settled in bulk, and bucket-of-money value transfers are processed in real-time but there is no money movement.

Bank rails

- to the sender and receiver, all payments are discrete

- perception of payments is real-time

- individual money movements

- both parties generally know each other

- payments move across a central hub

Card rails

- to the sender and receiver, all payments are discrete

- perception of payments is real-time

- bulk money movements

- parties generally don’t know each other

- merchants receive bulk settlement / cardholders pay against statements

Bucket of Money

- to the sender and receiver, all payments are discrete

- payments are in real-time

- individual value transfers

- parties might or might not know each other, it’s not significant

- money doesn’t move

Horses for courses

… and jumpers for goalposts.

We have, in the above, three different approaches to transactional payments: Bank Rails, Card Rails and the Bucket-of-Money. Like Football and Rugby, they all present similar approaches to the same given challenge, that of moving some representation of value from one place to another, but like Football and Rugby, they are not interchangeable.

Bank Rails, or account-to-account transfers are designed for pushing value from one account to another account, where the other account is already known. The sender knows the account details of the receiving account because presumably, the owner of the receiving account has provided them.

Push A2A transfers are ideal for the likes of HMRC, and similar operators of account-based services. The account holder is always in control and transfers value as and when necessary, and payments made are unlikely to be time critical.

Card Rails were alwaysintended for retail purchases, primarily where neither party to a transaction knows the other, which is why the elements of the transaction (cards and terminals) are designed to provide the necessary trust.

Merchants are guaranteed funds immediately on receipt of a successfully approved authorisation request, which means that they do not need to wait for confirmation of monies being received. Merchant settlement can then be provided for the whole business day, in much the same way as cash payments in the till are collected and counted at the end of the day and then deposited as a single amount.

Bucket-of-Money transfers fall outside the bank rails and card rails models as the movement of value isn’t matched by a corresponding movement of money. The initiation of a value transfer, or payment is therefore proprietary to the platform holding the bucket of money.

Payments are instantaneous as there are no money movements, and since merchants and customers are all connected to the same cash account, triggering a value transfer is simplified.

Three Money Movement Models – One Conclusion

Hopefully, we have established that it isn’t “only a payment”, that there are fundamental differences between the money movement models and that the reality is that payment scenarios are often better suited to a particular money movement model.

This, however, is not the conclusion.

The conclusion here is that whichever money movement model is best suited to an individual payment scenario, it is not going to be feasible to add another money movement model on top.