Magstripe Security Features

Magnetic Stripe Cards were first introduced in the late 1960s, following Forrest Perry, an IBM engineer, applying a magnetic stripe to a plastic card to record static data. The magstripe card became widespread for ATM cards, Payment Cards and Identity Cards throughout the 1970s.

In 1971, the American National Standards Institute (ANSI) established Track 1 and Track 2 standards, and the US has stuck with Magstripe ever since.

In the early days, card technology was new and ahead of criminal capabilities, but times changed and the crims began to catch up. What followed was a series of card enhancements, each addressing a particular vulnerability and each designed to keep the banks ahead of the game.

When I started, I was much more involved with Visa than I was with Mastercard. Let’s take a look at the security features that I remember being implemented.

Note: not all the Read More links are complete.

The LUHN Check Digit

The Luhn check digit is the final digit of most card numbers (like credit or debit cards), and it’s calculated using the Luhn algorithm, which is a simple checksum formula used to detect errors in identification numbers.

The Luhn check digit is designed primarily to detect card keying errors, specifically where two of the digits have been reversed in error. Whilst this function is primarily used to ensure the integrity of the card data as it’s keyed, it also helps to prevent card-related fraud facilitated by the random generation of Primary Account Numbers. In the early days of card numbers, this would have been a reasonable deterrent as it would have required a manual calculation.

A tamper-evident approach for the Signature panel

The signature panel on the back of a payment card, or a cheque guarantee card in the dim and distant, serves as both a fraud deterrent and a verification device. Cardholders are instructed to sign the back of the card on receipt, so that merchants may compare the signature on the card with that on the sales receipt.

The signature serves to authenticate the cardholder when using the card, and the connection between cardholder and card would be compromised if the signature could be easily replaced by a fraudster. Most, if not all, signature panels are designed with some sort of tamper-evident security feature: if someone attempts to erase or alter the signature, a hidden word – usually VOID – will appear in the background.

High coercivity magnetic stripe cards

The magstripe on a HiCo card is designed to offer greater durability and resistance to accidental erasure. A higher strength magnetic field is required for encoding, which makes the encoded data less vulnerable to being erased or corrupted by stray electrical or magnetic fields.

The HiCo card was introduced primarily for its resistance to erasure, but the equipment needed to encode the cards was harder to come by and therefore more expensive.

I don’t believe that HiCo cards were ever mandated by the schemes, but I do remember them being introduced, and they were regarded as an anti-fraud measure.

The Hologram

Holograms were introduced in the early 1980s as a visual anti-counterfeit measure. As card usage grew, so too did the incidence of card fraud, including the production of counterfeit cards. The hologram provided a first line visual check against fake cards, and made cards significantly harder to replicate with standard printing techniques.

Mastercard introduced the now iconic globe with interlocking rings in 1983, followed soon after by the dove in flight added to Visa cards, which again became an iconic hallmark of the brand.

In the UK, local debit cards were protected with a holographic headshot of William Shakespeare.

The border around the Visa Logo

I don’t know how I came to be reading Visa specifications but I was. They were printed and provided in around twelve substantial volumes, and they were supplemented by Visa Member letters and bi-annual updates.

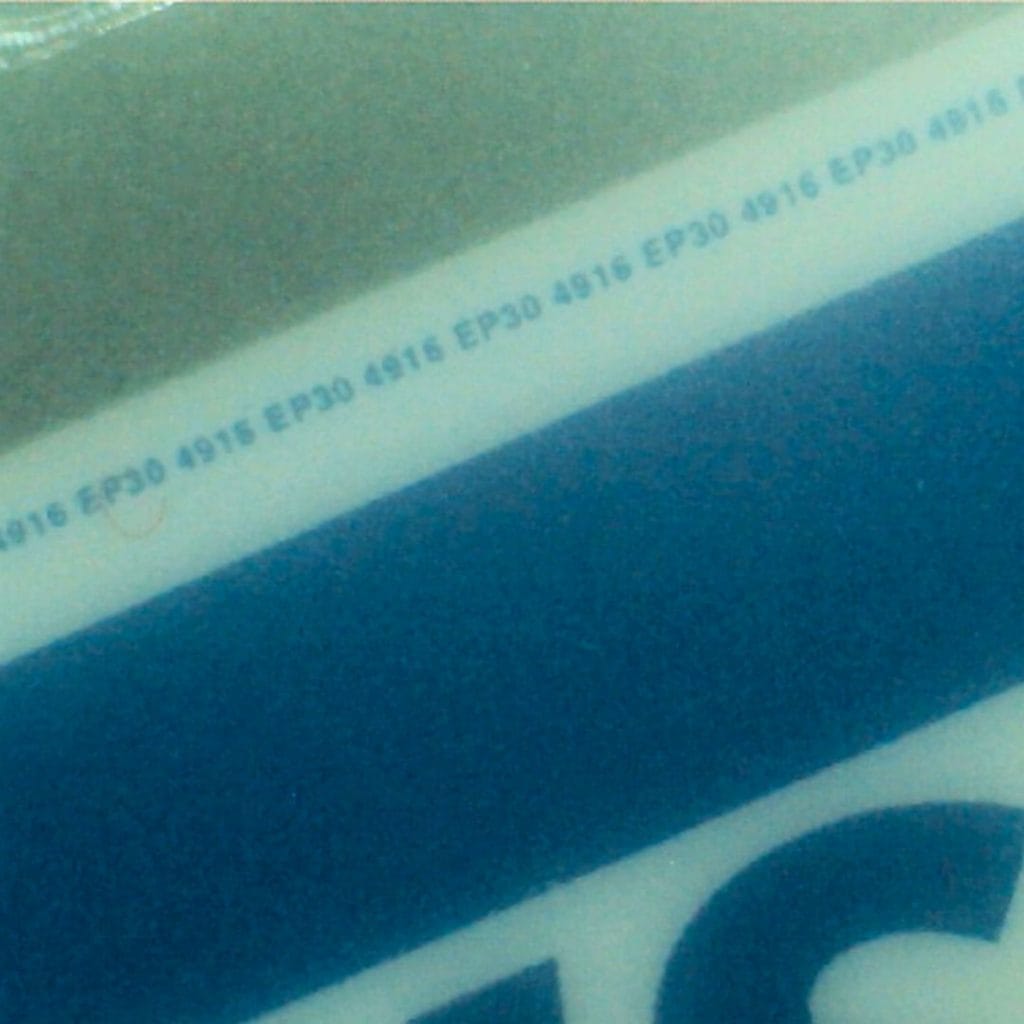

There were a lot of little features, hidden in the design of the physical cards, that could only be discerned with the aid of a magnifying glass. One example is the faint blue border that surrounds the Visa logo. If you look closely, you will see a 4-digit number alternating with some other letters and numbers. I don’t know what the other numbers and letters represent but the 4-digit number is always the first four digits of the Primary Account Number.

The four digits are 4916, and the BIN is 491624, issued by MBNA.

A sneaky addition to the look and feel.

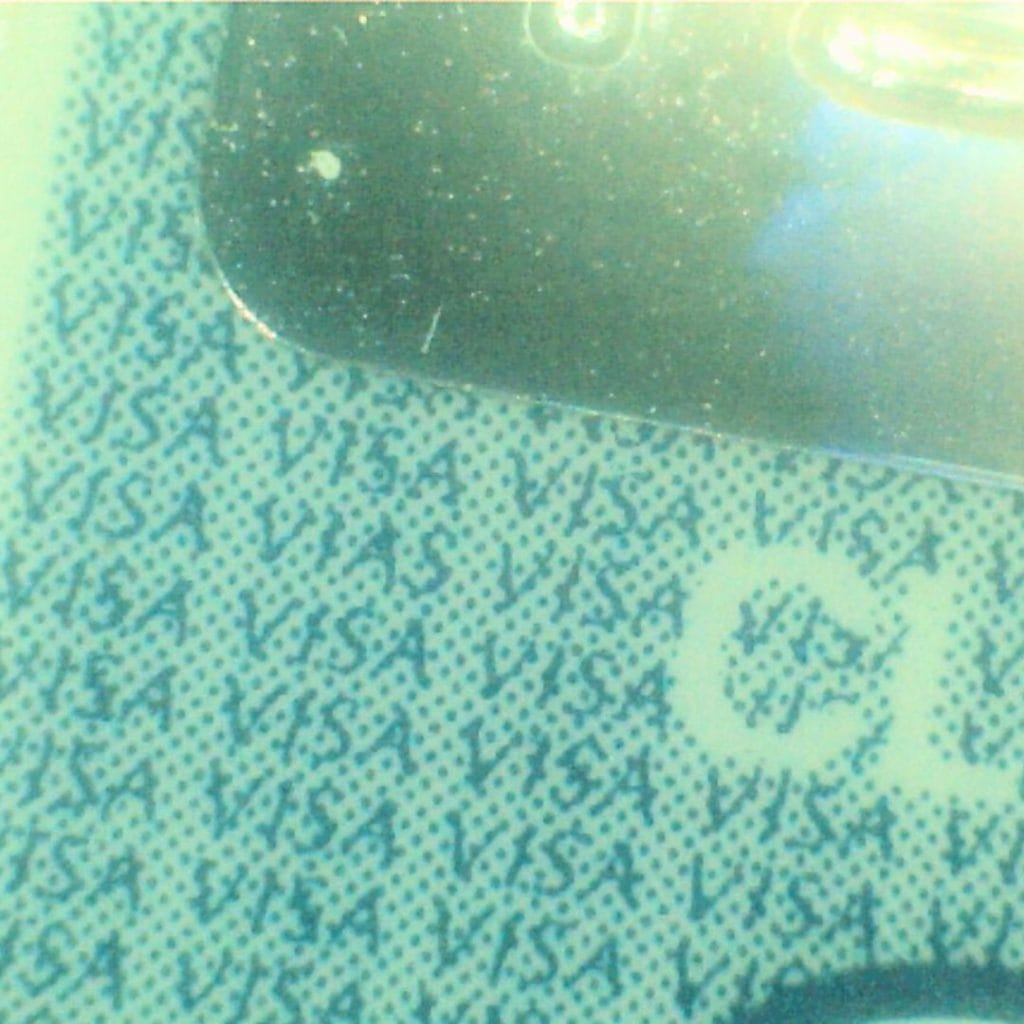

I like this one, and I remember reading about it in the Visa manuals. Look closely at the Classic Visa card and the tiny Visa logos that surround the hologram, and you will see that the word VISA is replaced, in some places, by an alternative spelling of the word: VIAS. Look closely – it’s in the second column from the left and the second row down from the silver of the hologram. It also appears elsewhere in the panel.

They are hard to spot, unless you know that they are there and where to look for them. I guess this is the point and adds complexity to the card. You would need to know about them and their position if you wanted to produce an undetectable counterfeit copy of a card.

The introduction of the CVV

There was a time when the only requirement for Track 2 on an ATM card was the Primary Account Number (PAN) followed by a field delimiter (“=”), and sometimes the Expiry Date. Credit and Debit cards usually included some additional data but at the time, magstripes could be created from the digits embossed on the front of the card.

The CVV was a 3-digit number derived from the PAN, the Expiry Date, the Service Code, and a secret key; the CVV was added to the Discretionary Data field on Track 2. The CVV was only available to the issuer host and was not permitted to be stored on any systems. It was passed across the networks as part of the Track 2 data field.

The CVV meant that to create a payment card, a doner payment card would have to be swiped.

Introducing the CVV2

The CVV was successful in reducing the number of fraudulent cards used in Face to Face transactions, but MOTO and ecommerce fraud was rising. You didn’t need the physical card; all you needed was the PAN and the Expiry Date.

When it was added to the signature panel on the rear of the card, the CVV2 limited the ability to use old card data (e.g. from used ZipZap vouchers) to procure goods remotely.

The CVV2 used the same algorithm as that used for the original CVV, but with one of the digits of the Service Code being replaced by a different value.

Ultraviolet Imagery on the Front of the Card

Ultraviolet (UV) imagery on the front of plastic payment cards was a subtle security feature used to combat counterfeiting and enhance local card authentication.

Similar to the UV features on banknotes, the UV-reactive elements are invisible under normal light but become visible when exposed to ultraviolet (black) light.

The use of UV imagery on the front of the cards appears to have declined in recent years, but can still be found on some signature panels.

Preventing ATM skimmer attacks with the jitters

Jitter technology is designed to make it more difficult for illegal card readers, known as skimmers, to copy credit and debit card data successfully.

The Jitter Technology is incorporated into the motorised card path of an ATM and distorts the readout of the magnetic stripe by altering the speed or motion of the the card as it is pulled into the card reader.

This makes reading the stripe using a skimming device mounted in front of the legitimate card reader near impossible as the jitter distorts any data that might be produced.

Sealing the legacy of magstripe with the PCI-DSS

I can read cards at my desk, and for a few dollars more, I could write them too – so could anyone else!

The CVV (not CVV2) prevented the crim from being able to create a card with only the embossed data, but authorisation messages and merchant databases were fair game – pretty much everything was in the clear.

The PCI-DSS was introduced to limit the crim’s ability to harvest card data in transit (captured from F2F authorisation messages) and at rest (from merchant and bank databases).

The PCI-DSS ensures the legacy of the magnetic stripe will live on way past its sell by date.

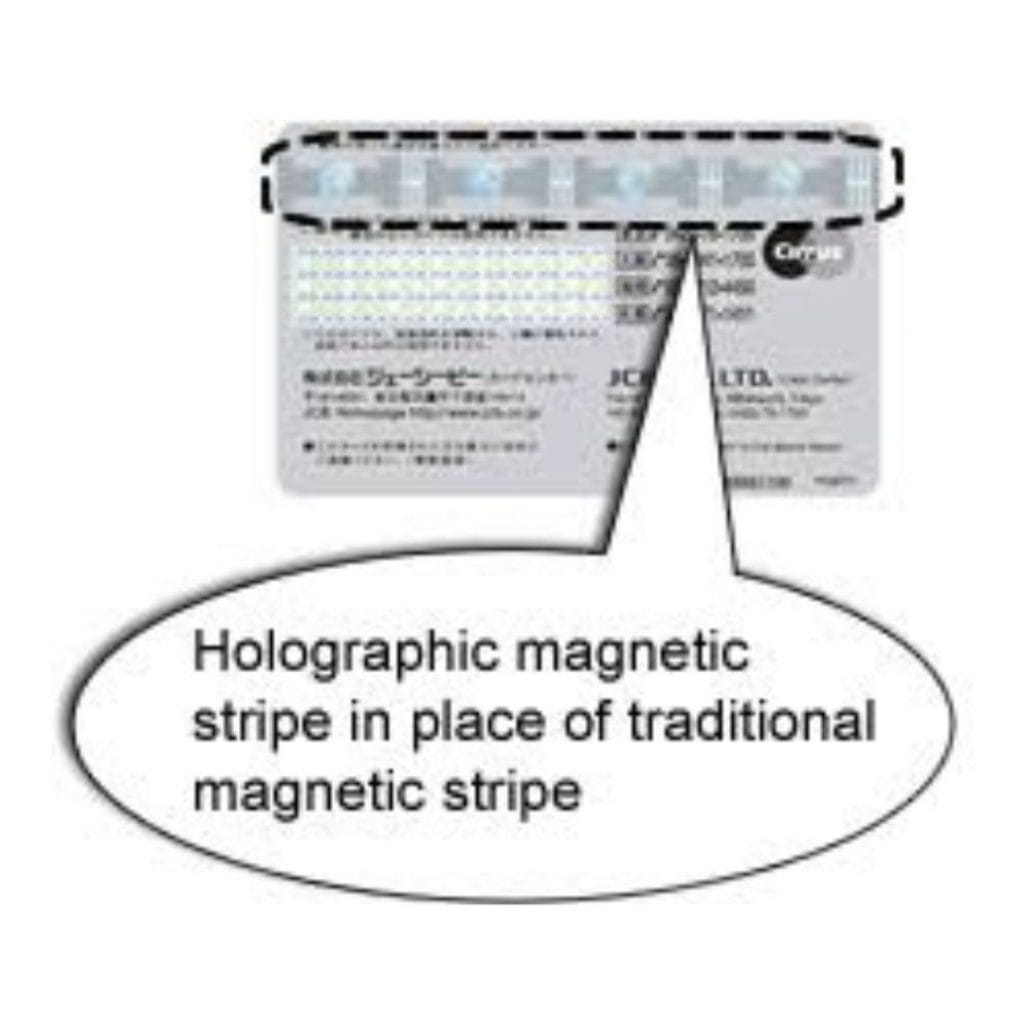

The Holographic Magnetic Stripe

This one arrived perhaps a little late to the game. Sometime towards the end of 2011, JCB announced that they would be expanding the the issuance of holographic magnetic stripe JCB cards, starting from 2012! This was around a decade after the launch of EMV chip cards in the UK, Europe, Australia and Canada – and several years after a similar move to chip in Japan!

The need to continue protecting the magstripe essentially evaporated with the introduction of chip cards, except for those regions that opted out.

Explore the Future of Payments

The global payment ecosystems continues to evolve with technologies like AI, tokenisation, and real-time payments.

Stay ahead of the game by diving deeper into the world of payment processing.

Have questions or need expert insights? Contact us.