Kenyan Brides

Something occurred to me as I was looking at Gary Prince’s reference to a BBC News snippet about some geezer sending all his retirement money, in instalments, to a non-existent Kenyan bride. He had clearly considered the risks and rewards, and the warnings from the bank, family and friends, and he had concluded that he was making a sound investment in his future, and that he was going to benefit!

Distribution of Intelligence

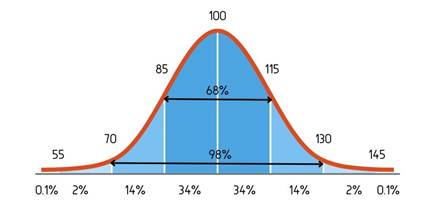

Plotting intelligence on a graph (it doesn’t matter how you measure it) will produce a normal distribution curve, and for IQ, we apply the value of 100 to the midpoint. Someone of average intelligence is therefore going to score around 100, which is also the highest point on the graph as it is the most common score. If you now look at the area under the curve and consider it to be a representation of intelligence across the population, which it is, you then can’t help but think it’s telling you that a significant majority of any population is as thick as mince

Normal Distribution Curve – IQ

We should perhaps consider this when we are congratulating ourselves on devising and delivering our clever interactive solutions and services.

Shiny Objects

However, let’s not forget that the promise of a better life and financial security, with the prospect of companionship and community thrown in, are certainly compelling reasons for optimism and for casting caution to the wind. Given the suggestion of personal improvement, happiness and the possibility of so many new and shiny things, it’s not surprising that people are reluctant to heed a little practical advice, choosing instead the rose-tinted alternative to prescription eyewear. In no way, however, does this absolve the sucker from taking responsibility for their decisions.

Everything in Perspective

Now, let’s take a step back and think ourselves back to the beginning of the new century and consider our own position in the world of card transactions and the prospect of shiny futures.

Across the world at that time, we were looking at an ever-increasing problem of card fraud. Magnetic stripes were so easy to copy and once copied, were indistinguishable from the original. I once wrote my ATM card details to the magnetic stripe on the back of an Argos Loyalty card, and yes, it did surprise some people because it was an Argos card, but it worked at the ATM.

We all knew that cards with chips were having an impact on card fraud, and that even included cards with chips but no chip data. The evidence was clear, card fraud was on the rise, but cards with chips were successfully limiting its progress.

We all understood that responding to card fraud was not going to be cheap, but we were in it for the long haul. We were looking to reduce card fraud systematically, and collectively, and we would have achieved it. After all, it had proven itself in the UK, and that same positive impact was being seen in every region that chip was being implemented. It was clearly the way to go, and it was you might call a no brainer.

Listen to the Experts

But then the US waded in, telling us what they had been telling us for years, that the magstripe card was the epitome of secure because all authorisation requests were approved online. We all know this was nonsense, and why it was nonsense, don’t we?

The fraud statistics were available for all to see. We could all see them, and we all understood that wherever chip cards were implemented, card fraud moved away. The statistics didn’t lie, in every case it was also clear that the fraud moved to magstripe land and regrouped.

So, we knew that magstripe fraud was on the increase and we knew that this was partly because the number of card transactions were on the increase, but mainly because magstripe cards were so easy to clone. The PAN and the associated cardholder data became accidental targets in the fight against fraud where the issue was the ease by which the data could be copied. This could be explained by the fact that the PAN and cardholder data encoded into the magnetic stripe was static, with no dynamic element, and the fact that cloned cards were not obvious clones.

The alternative was well known, if not fully understood everywhere. The alternative to the magnetic stripe was a card – and transaction – that included dynamic data, keys that couldn’t be extracted or copied and a form factor that pushed the ability to copy beyond the capabilities of most fraudsters, and this was available for all to see, and it worked!

It was clear at the time that we were going to be presented with two alternative card fraud solutions. One of them was a long-term solution that addressed the root cause of the problem, and the other was a cheaper – initially – solution that treated only the symptoms and could never cure the disease. In this, the “cheaper” option, a long-term treatment regime would be needed that would necessarily continue draining cash for ever.

It makes no Sense … does it?

However, even with all the evidence and advice, card industry professionals were choosing overwhelmingly to allocate their budgets to the card processing equivalent of the Kenyan bride; they even paid in instalments and were happy to do so.

The Payment Card Industry elected to take the lead from the US: the third world of card payment technology. The facts were there, and they were very clear – why would you ever think that legislating to protect the information freely visible on EVERY plastic card issued, ever, was going to be a good idea? In the face of all the evidence, decision makers of the payment industry went with it, and no amount of common-sense arguments was ever going to change that.

As Mark Twain may or may not have once said, “It’s easier to fool people than to convince them they have been fooled”.

The only difference is that in the case of the marriage scam sucker, the money that disappeared was his own, in the case of the corporate sucker, the disappearing money belongs to others.